Next time you enjoy a bit of cheese, consider whence it came, and what it took to get here. That innocuous rectangle of plastic-wrapped, odorless, evenly textured industrially-produced cheddar is one of those modern foods that is easy to eat because we do not see it being made.

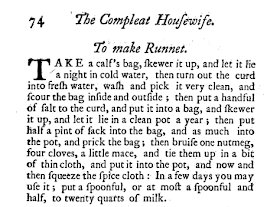

Today, it involves lots of metal in a factory and workers in masks and latex gloves, but in 1742, it was made at home by ladies with strong stomachs. Actually, they made it with newborn calf’s stomachs, as you can see (they call it a “bag”).

Stinging nettles are used to wrap the cheese because they contain a rennet-like coagulant which helps the cheese to form. Rennet is the enzyme that allows milk to become cheese, as opposed to simply rot. Today, cheese is made using the by-products of the veal industry for cow's milk cheese, though lamb's stomachs are used for making sheep's milk cheeses, goat's stomachs for goat's cheeses, and so on.

Vegetarians and those keeping Kosher need not despair however; a number of vegetable-based rennets are available. They are made from mold. On the other hand, some of the bacteria, fungi and yeast that comprise this mold have typically been modified with cow genes. Up to 90% of the cheese on your supermarket shelf is made with Chymax, a synthetic rennet made by the pharmaceutical company Pfizer.

It's important that the calf be slaughtered before it has been weaned so that its stomach has not been introduced to elements that change the type of rennet it produces.

Cottage cheese is so-called because it was a relatively quick variety of cheese to make at home, requiring far less stroking and curing than the solid cheeses. Cheese, like people, tend to sweat when not refrigerated.

The Compleat Housewife, Eliza Smith, 1742

Also from this book: Poxy Lady, A Cure For Cancer, Praise The Laud!, Fertilizer, Cock Ale, Chanel No. 2, Very Game